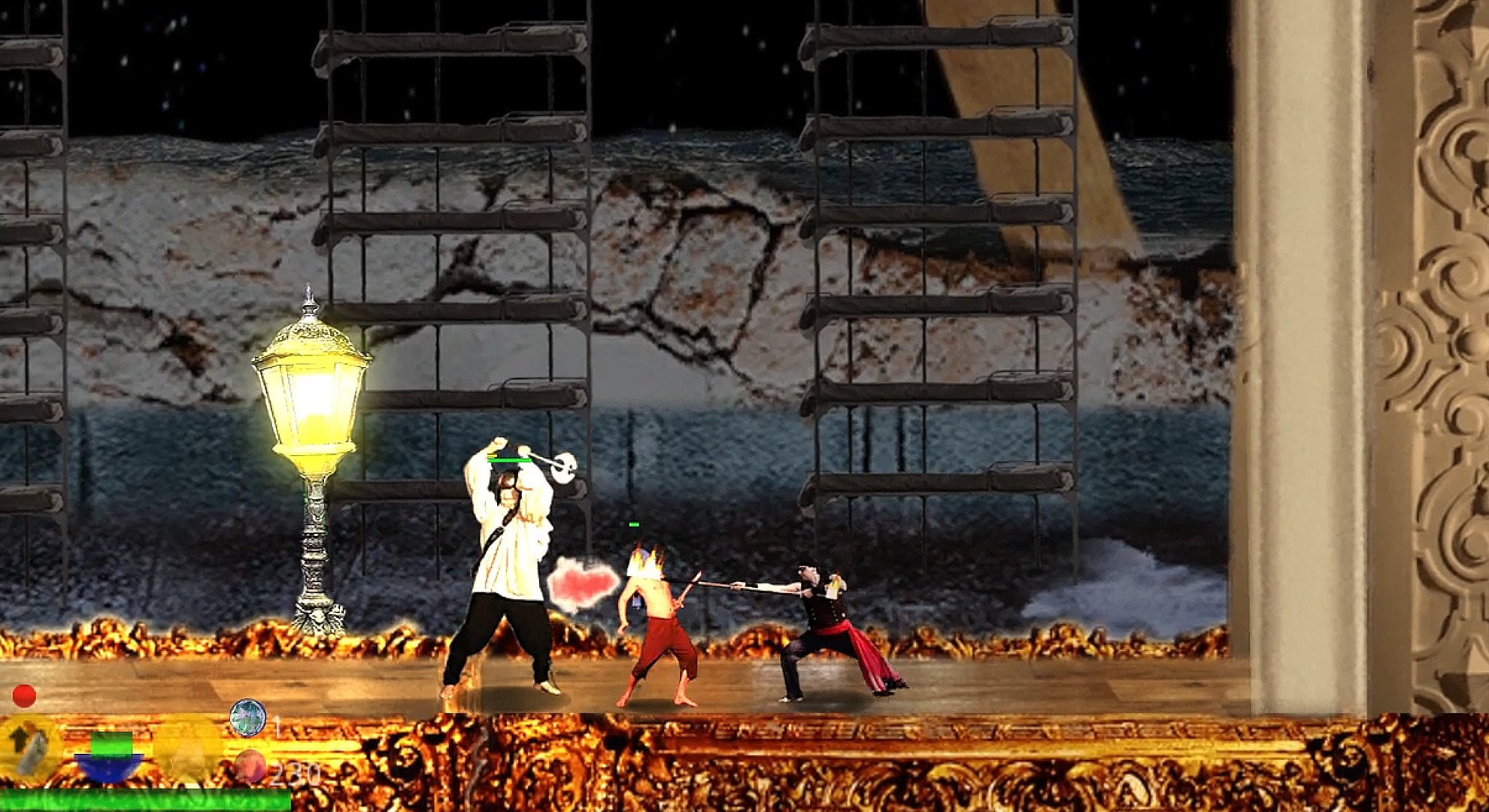

In recent years, FMV games have made a big comeback, thanks to critically acclaimed titles such as Her Story or the bizarre Blippo+. But one form of game art that has yet to resurface is digitised sprites, specifically the kinds that captured real footage of actors, such as in the original Mortal Kombat games. First-time game developer Charles Davis, however, is hoping to change that with debut game, Obey the Insect God.

Through his company Chunkle Freaky, Davis has actually been an underground filmmaker producing, writing, directing, editing, and acting in all manner of film projects, from features to music videos. As a day job, however, he also works in search engines, which was where his unexpected path to game development began.

The importance of Godot

Of course, the following year was when the pandemic hit, putting his next film project, Tender Kisses, on hold indefinitely (it was nonetheless finished in 2023). Stuck at home, depressed with too much free time, the programming Davis learned immediately found a practical application when he discovered the free open-source game engine Godot. “It uses something called GDScript, but it’s 99% Python,” he explains. “I was able to basically just jump in and start playing around with it.”

He however had no experience with computer graphics or modelling, yet with his filmmaking background, a green screen room in his garage, it meant he had to the setup to make digitised sprites, a medium that was familiar to him from his childhood in the 90s. So began the creation of this narrative-driven action game inspired by the Finnish epic poem The Kalevala, in which he cast himself, his wife, and friends from the local New York underground scene as characters. There was, of course, still the problem of figuring out how to implement digitized sprites.

“I could find lots of tutorials and stuff about making a normal sprite-based game, but for digitised sprites, there was just nothing, so I had to come up with a system,” Davis explains. “I would literally watch these old scenes on YouTube from when they were making Mortal Kombat 2 and 3. They have them on the green screen, they’re having them do the singular animations, and then they would show John Tobias photoshopping the individual sprites, so it looked like they were taking the clips, cutting each frame out as its own photo, and then them as sprites.”

Making use of After Effects

Fortunately, After Effects can actually download each frame of recorded footage into a PNG sequence, instantly giving Davis the images he needed to import into the game engine. At a modern 1080p resolution and 24 frames per second, it also meant these are much higher-quality, smoother digitised sprites than were possible on older hardware. But then he also had to learn the hard way that having a lot of large high-res assets also requires a lot of memory.

“Initially, I didn’t do any kind of compressing, and I had these animations that were ridiculously long, so when I started up my computer, it was taking 15 to 30 minutes for the engine to load because I was maxing out just running the player animation,” Davis explains. “I had to kind of come up with a bunch of rules for myself and how to manage the sprites because there were just so many of them.”

This included using a tool called Mass Image Compressor, which reduced the sprites’ size while retaining most of their quality so they could still be zoomed in on. Appreciating why so many game animations essentially use loops, he also imposed that no animation should be longer than between one and two seconds.

An FMV renaissance

There was still a complication towards the end of development: Davis discovered he had maxed out the engine’s memory pools, which led to the editor crashing. It’s an issue that apparently has been less common in Godot 4, whereas he has continued making the game on the older version of the engine over the past six years.

“I tried to transfer the game over to Godot 4 when it first came out, and the entire thing just broke, and at that point I was three or four years into development and I would basically just have to remake the entire game, so I decided to stick with it.”

Davis is hoping to follow the game up with another project with digitised sprites, and perhaps this may even kickstart a renaissance, or rather rehabilitation, for an aesthetic most people had written off. “To me, it’s more about trying to rediscover a lost art form because it was like this blip, and I feel like there’s still stuff to mine in this space from an artistic perspective,” he concludes. “As the Blues Brothers said, I’m sort of on a mission from God!”

Obey the Insect God is coming to PC in 2026, and you can try the free demo on Steam now.